Eliot Carter was my favorite contemporary composer. It was his first and second string quartets that opened my mind to the possibilities of linear melody/rhythm and the transformative nature of time. I discovered his music in my second year of music school and have listened to something of his every week since.

Eliot Carter passed last Monday, November 5, 2012. He was 103 years old.

Elliott Carter, the American composer whose kaleidoscopic, rigorously organized works established him as one of the most important and enduring voices in contemporary music, died on Monday in Manhattan. He was 103 and had continued to compose into his 11th decade, completing his last piece in August.

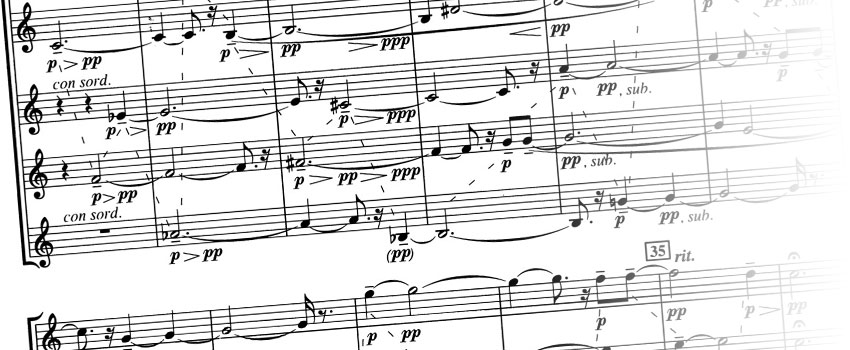

The String Quartets, of which there are five, are some of my earliest loves. The first time I heard String Quartet #1 was in the music building at Arizona State University. The room was quite cool, and the musicians were there to share their new repertoire, and some works that had been commissioned for them.

They decided to share the first movement of the first quartet, and I was simply blown away. I can only compare it to the first time I heard Coltrane… and my life changed forever.

They decided to share the first movement of the first quartet, and I was simply blown away. I can only compare it to the first time I heard Coltrane… and my life changed forever.

Many of the other music students there were aghast… where was the ‘melody’, why was the music so jarring. For the life of me, I had no idea what they had heard… but it wasn’t what I had heard.

I have nearly every recording made of the quartets, including a couple of imports. I even have the scores to both the first and second quartet.

Photography and music are two drivers of who I am. The polytonality and rhythmic challenges of Carter’s pieces fed my brain its much needed challenges, and it led to other discoveries, both in my music and my photography.

Mr. Carter’s music is not easy to listen to at first, especially for those who are not aware of the 20th century musical progression. But it is a challenge worth taking, in my opinion. Although, the meters and extreme difficulty of the performance of many of his mid-period works led to lots of angst among those who decided to take up that challenge, those who did found themselves quite transformed.

Listen:

String Quartet, First Movement

A Symphony for Three Orchestras

The Last Interview with Alisa Weilerstein

I performed his piece, Eight Pieces for Four Tympani, and it left me exhausted. And, exhilarated. The tempos ‘modulate’ through time as though it were a flexible substance rather than a temporal imperative. Damned difficult, and no, I could not play it today… heh.

Shifting meters, rhythm that was both polyphonic and amorphous, melodies that stretched over others with seemingly no relation… it was demanding stuff. And it made demands on the listeners that some were not willing to do. His music was not something most people would leave the theater humming to themselves.

Also from the NYT:

As Mr. Carter’s centenary neared, the frequency with which his music could be heard only increased, making it clear that for at least two generations of young performers, even his thorniest works held little terror. In the summer of 2008, for example, the entire Festival of Contemporary Music at the Tanglewood Music Center was devoted to Mr. Carter’s work, with performances of dozens of pieces from every stage of his career (including several premieres). Mr. Carter attended most of the concerts. There were many such tributes that year, and the attention unnerved him, he said.

“It’s a little bit frightening, because I’m not used to being appreciated,” he said in an onstage interview at Zankel Hall the night after a celebration with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. “So when I am, I think I’ve made a mistake.”

“Eventually Carter realised that all the accumulated baggage of his music – the neoclassicism, the madrigalian references, the Greek texts, the Americana – would have to go. In the Piano Sonata of 1945, written the year he moved with his wife into the brownstone apartment he would live in for the rest of his life, Carter retains the massive rhetoric of the American sublime. But the cyclic form, the startling use of piano resonances and rhythmic flexibility mark a huge step forward. The Cello Sonata of 1948 is another leap towards a really radical conception of form. The piece at the end seems to loop back to its opening, in a way that recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s conception of a book that one can begin at any point. At the beginning, a strict metronomic “ticking” in the piano is combined with a rhapsodically unfolding line in the cello. Nothing quite like this joining of two radically opposed worlds moving at different speeds had been heard in music before.

But it was in the First String Quartet of 1951 that Carter’s new conception of independent musical layers, sometimes co-operating, sometimes clashing in purposeful disunity, came fully into focus. To achieve it, Carter cut himself off from his usual surroundings and moved to the Arizona desert for several months. What survives from his old manner is a heroic rhetoric of wide intervals, as if the American sublime has been sublimated and purged of anything local.”

This music, so utterly grounded in a complex, and for me, an almost visual experience, made my journey into music both a fascinating and joyful adventure, and a disquieting and elusively disconnected vision of what I wanted to do. Both with music and photography.

It is that air of conundrum that drives me today as well.

“In many ways, Carter was cut from the same cloth as the Founders. Crossing back and forth across the Atlantic with his father, a lace importer, Carter spoke French before he spoke English. At Harvard, he initially spurned music, opting instead for Greek and mathematics and philosophy. He recapitulated some of the background of the aristocrats who founded the United States: a classical education with a French flair. He was a modernist equipped with the intellectual tool kit of the Enlightenment.

He came to be a composer in deliberate fashion; he was well into his 30s before he wrote music he thought worth keeping. It would be another decade before he began to realize his own style. The decisive break came in his first two string quartets, dating from 1951 and 1959, where the four players become strikingly individual characters, with their own motives, articulations, and even tempi, an intricately managed clash of temperaments. Almost all of his subsequent music would similarly straddle the line Thomas Paine drew between society and government: “The one encourages intercourse, the other creates distinctions.” Carter’s goal was to give every instrument in the ensemble its own individuality within the piece’s entirety. ‘‘This seems to me a very dramatic thing in a democratic society,’’ he said. In honor of the American Bicentennial, Elliott Carter even split the orchestra asunder, composing “A Symphony for Three Orchestras,” a work that, indeed, divides that ensemble into three distinct and often disputatious groups. It might have been only a coincidence that the onetime revolutionaries who assembled for the Constitutional Convention in 1787 came up with a similar model for the federal government.”

“Mr. Carter experimented most notably with meter, or rhythm, and challenged audiences to follow multiple instruments that played simultaneously to different beats.

“A piano accelerates to a flickering tremolo as a harpsichord slows to silence,” wrote composer and musicologist David Schiff, describing Mr. Carter’s music. “Second violin and viola, half of a quartet, sound cold, mechanical pulses, while first violin and cello, the remaining duo, play with intense expressive passion. Two, three or four orchestras superimpose clashing, unrelated sounds. A bass lyrically declaims classical Greek against a mezzo-soprano’s American patter.”

Mr. Carter said that his music presented society as he hoped it would be: “A lot of individuals dealing with each other, sensitive to each other, cooperating and yet not losing their own individuality.””

Yes… controlled cacophony. Distilled life sounds played out in a chamber or orchestral setting. Music to live by, think by… create by. Rhythms that seem disconnected from each other are found to have deep relationships after careful listening.

And this music is made for careful listening. It is not Mozart for background string melodies. Nor is it the driving, pulsating, deeply spiritual John Coltrane.

It is music for listening to as an action in itself, for involving ones self within each bar and linear melody. It is for “active” engagement, not background filler.

It is music for listening to as an action in itself, for involving ones self within each bar and linear melody. It is for “active” engagement, not background filler.

Perhaps that is what I found so totally and honestly engaging about Carter’s music. It demanded that you listen to it, not daydream or dance or plan the next vacation while it was on. LISTEN to each sound and melody and rhythm – and feel the complexity slide away to reveal simple, intimate truths.

Individuality of spirit is ensconced deeply into his works, and that wondrous spirit was a gift to us all.

If we take the time to listen for it.

I wondered how I would feel when I heard of his death. I know now.

I wish I didn’t.

“The American master, seemingly inextinguishable, died this afternoon, at the age of 103. An entire world of culture dies with him — a landscape of memory that included Stravinsky, Nadia Boulanger, Ives, Gershwin, even Gustav Holst.”

A truly great mind.

Yep.

It was a pleasant and eye-opening surprise to find this skillful and sincere tribute published on a photography website. Not being a music person, I admit I never had heard of Eliot Carter, but the writing made me interested enough to investigate. Even the brief samples available on Amazon make clear that this music is, as the article states, “made for careful listening” — and I plan to listen to some of it, which I certainly would not have done if it had not been for this essay.

And yet I suspect that during Carter’s lifetime, more-casual music enthusiasts — not to mention hard-working, gig-playing commercial musicians — would have dismissed this complex, cacophonous, not-readily-accessible work as nothing more than pretentious pseudo-intellectual fraud. No doubt there were some who dismissed Carter, and the critics who admired him, as ivory-tower intellectual BS artists perpetrating a snow job on a gullible public — much the same way that photo enthusiasts and commercial photographers often disparage and dismiss the complex and not-readily-accessible work that constitutes contemporary fine-art photography.

Yes, that indeed occurred.

Not as much as you would think, though, as Carter was very widely known in the contemporary composition circles.

But the public was indeed a bit resistant to that kind of music. Still is.

Our Symphony Orchestras still fill their concerts with easily digested music from over a hundred years ago. I could expound on the cyclical problem of not presenting new music so that new music is still a foreign sound. Sad.

For an entry to Carter, try the First String Quartet and the Variations for Orchestra. If you like what you hear, try the Concerto for Piano and Harpsichord and the Piano Sonata.

Hope you enjoy the music.

Thanks for the comment.

Beautiful! Magnificent! Genius!! Thank you for writing this blog, Don. Mr. Carter’s music is wonderful to “listen” to. He keeps you on your toes, like a good mystery.